Get Your Rust Belt Education, Right Here

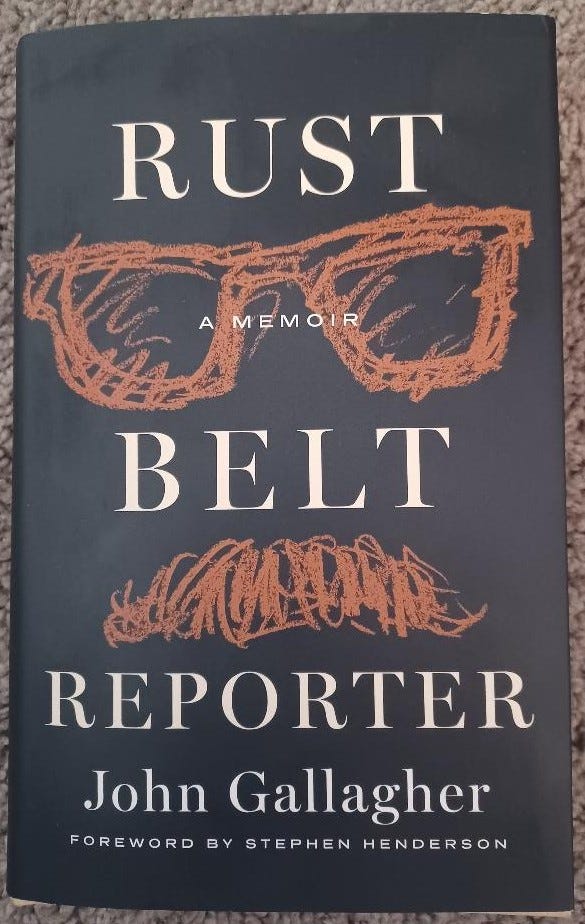

A review of the book Rust Belt Reporter, by former Detroit Free Press columnist John Gallagher.

Source: Pete Saunders

During its run, I absolutely loved the HBO series The Wire. It was a fascinating show that provided deep insight into the institutional corrosion that felled post-industrial cities like Baltimore. Each season featured institutions – the sad ubiquity of the illegal drug trade; Baltimore’s port system, and the union desperately trying…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Corner Side Yard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.