In Search Of Equitable Cities

When it comes to cities, our nation keeps looking outward, or upward. If we truly want better cities, we need to look inward.

Above is an aerial photo of the Detroit/Grosse Pointe Park municipal boundary in the Detroit metro area. The rise and development of Detroit’s East Side neighborhoods and Grosse Pointe Park (as well as the other Grosse Pointe communities) took place at the same time -- about 1880-1920. On the left side is Detroit, with hundreds of vacant lots that gives the area the appearance of a park. On the right side is Grosse Pointe Park, an affluent, still-built-out community well within view of the less affluent Detroit. This is how exclusion looks. Source -- Google Maps

Note: I’m the son of a preacher. I often heard my father relate a story in church that a pastor preached a sermon one Sunday morning that struck a chord with the congregation and set off the Holy Spirit. The following Sunday, he preached the exact same sermon, received a similar response, but provoked some curiosity. He did the same thing on the Sunday after that, leading to a very perplexed congregation.

Several congregational leaders decided to pull the pastor aside after church and talk to him about the repeated sermons. Why, they said, are you repeating the exact same sermon, every week? The pastor’s response: “When people start living the lessons of God’s Word from that sermon, I’ll move on to another one.”

Below is a post originally published back in 2023. I’m bringing it back because it expresses my thoughts on where our nation really stands with cities and their future: urban and suburban self-interests (YIMBYs and NIMBYs) vying for control of the urban development landscape, while ignoring the vast parts of our cities that would benefit from redevelopment, in the public interest.

In continue to believe the revitalization of cities happens when we stop trying to make new cities, or reimagining old ones. Truly redeveloping what we have already — physically, economically, socially — will help more places become stronger.

So I’m still preaching that sermon.

I saw two things over the weekend that reminded me how far away we are from having equitable cities in the U.S.

First, on X (Twitter), Arpit Gupta offered a particularly sunny view of how the near future would belong to American suburbia. His point? Over the next 10-15 years, the rise of EVs, renewable energy at lower costs, and the expanding WFH phenomenon would lead to suburbs becoming vibrant, full and complete communities:

Well, yes and no. I see many suburbs that will be more than willing to welcome the transformation Gupta puts forth. They’ll add density, mixed uses, maybe even transit that makes them much more like city neighborhoods.

However, there are many suburbs, perhaps even more suburbs, that will be slow to undergo this transformation, or would even reject it altogether. Why would some communities delay or reject transformation? One word – NIMBYism.

Before I explain, let me say that I have a sociological or humanist perspective on how cities are born, grow and die. Cities are social creations and are subject to limits of the societies that form them. It’s been pretty clear for decades here in America that we’re much better at looking out for individual interests than for the common good, and that’s reflected in our communities.

The NIMBY instinct to protect community character and uphold property values does not fade away easily. Suburban homeowners will continue to dig in on maintaining suburbs as they are. In fact, I envision suburban homeowners doing everything they can to recoup their investment, with the support of their elected officials – until they can’t.

And when that happens, another cycle gets kicked off. Homeowners will do their best to limit their losses. They’ll move away as quickly as they can and set many suburbs onto a path of decline.

A rationalist would suggest that recent trends favor a future that remakes suburbia into vibrant and complete communities. But we’re not talking about rationality here. We’re talking about American homeowners.

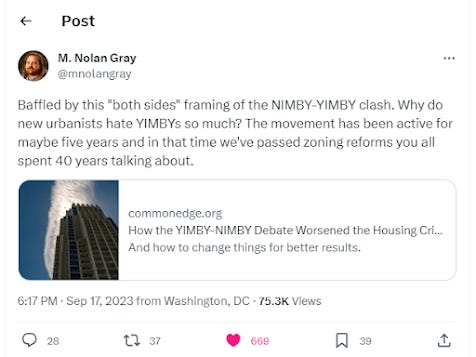

Second is a post from M. Nolan Gray on X about the NIMBY/YIMBY divide. Gray cites an article posted on commonedge.org written by architect Steve Mouzon, a New Urbanist. Gray takes exception to a critique made by architect Steve Mouzon, a New Urbanist, on commonedge.org:

Mouzon says that the housing crisis of the 2010s widened the split between NIMBYs (or at least, “good” NIMBYs) and YIMBYs.

A quote from the article:

“In their rush to combat NIMBYs tit for tat, point for point, YIMBYs blame the housing crisis on NIMBYs’ choice-limitation metrics: density, zoning, parking, etc. But these factors existed decades before the current housing crisis. Yes, they have always been used for racist and classist purposes against those less privileged, resulting in less affordable housing in decent places, but if they were the only factors, the current housing crisis would have begun decades earlier. It didn’t.”

Mouzon then ended his article with this word for YIMBYs:

“Ditch the confrontation-first approach and try to inspire better things instead. Some of your own are turning out reams of inspiring content every day; the only problem is that you only have a tiny handful of these colleagues … so far. And especially be sure to get rid of the narrative that your mission is so righteous that nothing can stand in the way of your metrics, especially anything that might be confused with aesthetics. Because that’s an architect-spawned slur against places people love. There are reasons for hope today. See them.”

Being an architect, Mouzon’s interest is in building beautiful and sustainable communities. It seems he sees the YIMBY focus on increasing housing density to create more affordable housing as a case of “the perfect being the enemy of the good.”

For what it’s worth, Gray disagrees with Mouzon by stating that YIMBYism emerged well after the housing crisis, coming together really over the last 10 years. Gray also notes that YIMBY’s zoning deregulation activism – upzoning to generate more new housing units – has led to more policy reforms over the last five years than New Urbanists have in the last 40.

Whatever. I don’t see this as a deep rift between New Urbanists and YIMBYs. New Urbanists want more traditionally-built, aesthetically pleasing communities, like what used to be built in America prior to World War II. YIMBYs want more housing built to bring housing prices and rents down from their stratospheric heights. Any squabble between them can be mended once suburbia, the dominant development type in the nation, embraces the transformation that would allow both things to occur.

But what about equity?

Let’s take a really long look at the development of American cities and suburbs. Over the last 125 years or so, I find three broad trends that characterize the American built environment: 1) the migration to cities as the modern industrial economy developed; 2) the explosion of suburban sprawl that settled a new American frontier and strengthened the nation’s middle class, and; 3) the rebound of cities as primary economic engines in the new knowledge and information economy. Each trend brought benefits with them (for example, a more prosperous and comfortable nation for the majority of Americans) yet also exacted costs (like the loss of traditional incremental development in favor of large-scale, single-use subdivisions, and the rapid rise of housing prices in the cities at the forefront of the knowledge and information economy).

One cost, however, has been constant throughout, threading through all three trends – inequity. The early 20th century city urban migration created impoverished city neighborhoods as well as wealthy ones. The midcentury suburban expansion effectively codified inequity through exclusion. The return of wealth to cities in the 21st century has probably led to more city residents being uprooted rather than included in the most significant economic transformation of my lifetime.

I look at New Urbanism and YIMBYism, and I see movements that, unconsciously and unintentionally, continue to promote inequity. The attention to design and detail needed for New Urbanist developments means they’ve largely been built for upper-middle class or wealthy residents, in upper-middle class or wealthy communities. Upzoning can spawn new housing development, but upzoning also kicks off a race by developers to serve the wealthiest first and others later, if at all.

I’ll put this another way. The exclusion of Blacks, immigrants and other people of color in American cities has never been resolved. It prevents cities from reaching their fullest potential. It’s been tempered over the years, but it still exists.

I’ve yet to see any urbanist movement directly take on what I view as the most critical long-term challenge facing cities: their inequity. Until there is, it will always be with us.

My impression was that YIMBY’s want to solve one particular problem, which is that there are too many restrictions on building, and they rationally want that to be seen as a non-partisan issue. My understanding is that YIMBY’s on the left then hope that the changes in zoning allows for governments and non-profits/churches to do things like building affordable housing, in addition to allowing developers to provide new housing where the wealthy can dump their money (instead of on existing housing).

Thank you. Your observations dovetail perfectly with my experience in Kansas City.