Land Developability And Housing Costs

YIMBYs are right to pursue options for increasing housing development. But we can't look to past methods for answers.

A view of a housing subdivision in Garland, TX, 15 miles north of downtown Dallas. Source: gettyimages.com.

A note to readers:

After going to paid subscriptions in mid-March, many of you signed up and I’m grateful! I’m absolutely delighted that there’s a growing audience supporting the content I love to produce, and I thank you. However, about a month into the new subscription phase, I started a new position that limited my ability to produce content for a while. Rather than limit the content behind a paywall, I decided to make all content available for everyone until I was able to get a handle on things at the new job.

Now I’ve gotten things reasonably under control. Beginning Monday, July 7, I’ll resume producing content behind the paywall again, as well as for my general audience. Until then I’d invite you to take a look a more than 750 articles in my archive while you can, and make what I hope is the decision to sign up to the Corner Side Yard, either as a paid or free subscriber.

Join now!

Back in April, Conor Dougherty of the New York Times wrote a thought-provoking essay in favor of suburban sprawl as a solution to the nation’s housing crisis. Dougherty brought up the California experience, where housing construction slowed while population kept rising. The tactics mastered in California became the tools for the NIMBY movement:

“Consider the trajectory of California. In the 1960s and ’70s, when the state added eight million residents and fruit trees were being ripped out to make space for ranch houses, its Legislature passed a flurry of land-use and environmental laws aimed at preserving agricultural land and containing development to major metropolitan areas. Those laws were celebrated for saving farming regions like Napa Valley and wild spaces like the Marin Headlands, but they also have made building so difficult that even environmentally friendly projects, like a small apartment building next to a commuter rail line in San Francisco, can be tied up in years of lawsuits that can add millions of dollars to the final cost.

Similar laws throughout the country have slowed the pace of construction and made housing far more expensive, contributing to one of the worst affordable housing crises in the nation’s history.”

Meanwhile, Dougherty also tours suburban Dallas, one of the fastest-growing metros in the nation. He goes on a helicopter ride north of Dallas to see subdivisions sprouting up faster than prairie tallgrass:

“The helicopter made a dusty landing about 40 miles from downtown Dallas, in an area where builders were laying down new traffic circles next to pastures grazed by herds of longhorn cattle.

Hillwood is a land developer that creates planned communities, building infrastructure and dividing up lots that major homebuilders like D.R. Horton and Pulte Homes then fill with houses. The executive took me around one of the firm’s projects, quaintly named Pecan Square, which has a faux downtown complete with parks and pickleball courts; a co-working space on the square has been built with exposed ductwork, to give it an industrial vibe. Once finished, Pecan Square will have 3,100 homes, starting around $415,000 for a three-bedroom.”

The question looms large – how is Dallas able to build so many homes, at such affordable prices, to actually meet the region’s growth demand? Dougherty’s position is that development has been made so expensive in so many regions across the nation, driven by local government land use and state-enacted environmental laws that make construction prohibitive, Texas, he notes, has no such qualms with growth, and continues to benefit from it. Dougherty seems to move toward a grudging acceptance of suburban sprawl as a solution.

But what if comparing, say, the Bay Area with Dallas is a completely unfair comparison?

One of the often-used arguments from advocates for increasing housing supply in our nation's most expensive cities is that zoning policy, or the regulation of land use by local government, has kept an artificially low ceiling on housing development, partly enabled by NIMBY homeowners who decry any changes that alter their community character -- or property value. There is quite a bit of truth to this.

But there are two counters to this argument that get little attention. First, there are actual physical, geographical, and social limits to development that go unrecognized, or increase the level of difficulty in adding more housing. Second, whether we like it or not, the American preference for development intensity has declined over the decades, leading us to view sprawled development as fully developed.

Taken together, it’s clear that simply lifting restrictive zoning standards alone can’t resolve our nation’s housing affordability crisis.

See these numbers? Back in 2010 a group of geography researchers gathered data on land development availability. At that time they found that the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area had a little more than 1,700 square miles of total land that could be developed, or just under 25 percent of the total land area for the metro. Meanwhile, metro Dallas had more half of its land available for future development.

The numbers go a long way toward understanding why development costs are much lower in Metroplex when compared to the Bay Area, and why suburban sprawl is acceptable option in Texas.

The data you see above comes from a research project completed 15 years ago by a team of geography researchers from Penn State University. The researchers, led by Dr. Guangqing Chi, then an associate professor of sociology and demography at Penn State University; Dr. Derrick Ho, then a research fellow from Hong Kong Polytechnic University; and James Beaudoin, a geographical information systems/web developer then with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, created a Land Developability Index quantifies the approximate amount of land available for development across the nation, down to the county level. To arrive at their numbers, they factor out the following surface types generally avoided through new development:

· surface water areas;

· wetland areas;

· federal and state-owned lands (parks, forests, preserves, wildlife refuges, fisheries, etc.);

· estimates of steep slope areas (areas with a terrain slope of 20% or more) identified through satellite analysis; and

· analysis of existing built-up land, already occupied and built for human use.

In the Bay Area’s case it’s deeply impacted by the amount of steep slope from the hilly and mountainous terrain throughout the area. I don’t have exact numbers on steep slope land area, but it doesn’t take a genius to understand that the Pacific Coast Ranges – the Santa Cruz Mountains on the peninsula, and the Diablo Range in the East Bay – dramatically reduce the amount of developable land in the overall Bay Area. Bay Area residents get a fantastic quality of life benefit from the mountain views, but they come with a price. Dallas is not impacted in the same way. The rolling plains of north Texas are ripe for easy development.

It’s a matter of geography.

This is an issue that vexes much of the United States west of the Rocky Mountains and contributes mightily to the high cost of housing – and all development – in the region. Last week I came across this Substack article, in which the author Brian Potter questions why housing development costs so much in Western states. He brings up the cost of housing development in Sheridan, WY, a small town near the Montana border experiencing severe growth pressures:

“Sheridan is a town on the northern edge of Wyoming, very close to what I’d call the middle of nowhere. It has a population of around 18,000, and is more than 100 miles from any major city or international airport. And yet if you look at home prices, they’re through the roof. Basic suburban houses cost close to $300 per square foot. This is substantially more than the per-square-foot value of my home in metro Atlanta. Burley, Idaho is also a small town (population around 12,000) far from any major metro area, with the cost per square foot of new homes in the $230-$250 per square foot range. Both cities have seen robust growth: 18% and 25%, respectively, between 2000 and 2020.”

Potter is right to mention that the town has experienced strong recent growth. However, a quick check of a terrain map would explain quite a bit about rapidly rising housing prices in a small town:

I’m sure Sheridan enjoys great mountain views. But by being nestled into a valley, it’s geographically constrained; it has natural limits to growth and development. Unfortunately, Potter makes no mention of this constraint.

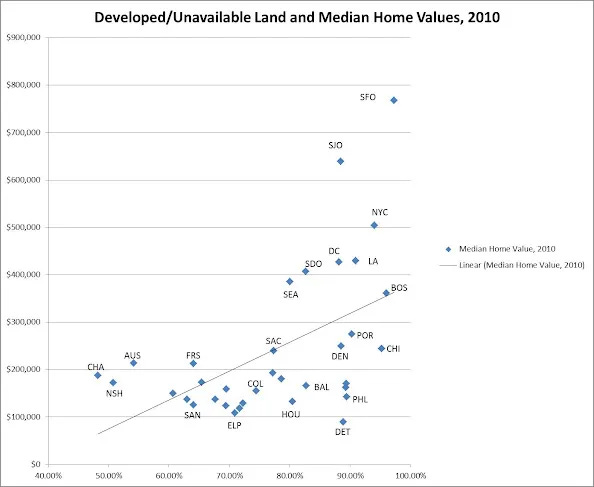

When I first wrote about this some eight years ago, I put together a graph that shows the relationship between the amount of developed land and housing prices, using the 2010 data:

Sure, the data is old but I think the relationship still stands. The "superstar" cities of the east and west coasts occupy the highest rungs of the chart on the upper right, with the highest percentages of developed and unavailable areas and the highest home values. The bottom right area is occupied by largely built-up areas that don't have the high-powered economies that boost housing demand (Philadelphia, Detroit) or low-cost cities that are still growing but have plenty of room for future growth (Houston, Dallas, Phoenix). The bottom left includes cities like Charlotte, Nashville and Austin that have might show value speculation out of proportion with their available land. And the upper left? Probably reserved for the city comprised exclusively of palatial estates with plenty of land to spare. In other words, empty.

Let’s return to the Bay Area/Dallas comparison. Sixty years ago, the Bay Area did exactly what Dallas is doing today. Without any consideration of any development constraints, it built out a sprawl paradise. The Bay Area, however, had a natural limit that Dallas does not. Honestly, I agree with YIMBYs who want to build up in West Coast metros; it’s the only way actual affordability can be achieved. Wishing for a return to sprawl, however, is misguided. Just because sprawl can happen doesn’t mean it should, and Dallas will one day likely experience the negative aspects of its growth profile. I’ll explore more of that soon.

I think that this argument indicates that even if the coasts massively up zone, they still are going to be more expensive than interior cities, just because those cities have so much more land? Tearing down existing buildings and then building larger buildings is much more expensive than greenfield building. If states and metros like Charlotte make land use reforms right now such that they can quickly and cheaply build multi family and townhomes on greenfield sites, I would think that they would continue to be affordable for a far longer time than anything on the West Coast.