Middle Class Reimagination

Today's service class deserves the same kind of economic infrastructure that made middle class households out of manufacturing workers.

Jeremy Allen White, star of the Hulu/FX series “The Bear”, awaits the start of a dinner for the cast and producers of the show in Hollywood. Source: gettyimages.com

I love the television series "The Bear". Of course, one reason I love it is because it puts my city, Chicago, in the spotlight. But perhaps the chief reason I love it is because it looks at how a city like Chicago turned its proximity at the center of the nation’s breadbasket into 19th and 20th century successes in food production and processing, and more recently into upscale hospitality. Today, Chicago is recognized as one of America’s top foodie destinations, in terms of its quality and diversity. I also enjoy it because it recognizes that talented, creative and innovative people are working in fields that cater to the whims and desires of the wealthy, yet earn a fraction of what the wealthy make. They could – should – make more, but satisfaction in their craftsmanship is perhaps their greatest reward.

Six years ago I was fortunate to be a part of an interesting symposium, and it came back to my mind while thinking about The Bear. It was called Policies to Promote Inclusive Urban Growth, and the symposium coincided with the public release of a report, Beyond Gentrification: Towards More Equitable Urban Growth, published by the Center for Opportunity Urbanism. The report took a look a recent development activity and their impacts in three very different cities: Chicago, Los Angeles and Dallas. Each city has had some measure of urban success, but each has had significant failures that, if left unaddressed, threaten the very future of the cities.

Our research team found that Chicago is steadily becoming more of a bifurcated, rich/poor city. We found that Los Angeles' high rents are making it incredibly difficult for middle income residents to afford reasonable places to live, and high home prices are preventing the transfer of wealth through homeownership. Dallas' middle class is imperiled too; it's perhaps just as bifurcated as Chicago is, but its bifurcation is often masked by strong economic and residential growth. Sadly, those trends haven’t changed much in either of the cities over the last six years.

The key theme of the report was that as American cities stepped up their pursuit of the upscale creative class, the upper middle class collection of professionals in fields like technology, finance, the arts, and other fields that rely on creative and critical thinking, those cities neglected the middle class. We faulted cities for not developing the middle class, and used a Jane Jacobs quote:

“A metropolitan economy, if it is working well, is constantly transforming many poor people into middle class people, many illiterates into skilled people, many greenhorns into competent citizens... Cities don't lure the middle class. They create it."

...to make our point. In effect, Jacobs was saying that cities are escalators in the development of human capital.

But it’s probably more correct to say that over the last 25-30 years, cities have moved away from that approach. The 21st century back-to-the-city movement doesn't at all represent neglect of the middle class, but of the city's newfound ability to compete with suburban areas for the upscale market. And cities were forced into this switch, because the middle class as we know it simply isn't being developed anymore.

I'm leaning more toward the belief that cities themselves have little to do with the development of the middle class, at least in terms of income. There is certainly a pivotal role cities have in imbuing a sense of middle class sensibility to its residents, through its institutions and values. Middle class incomes, however, the financial means that begin the pursuit of middle class dreams and values, were the creation of national policy over the latter half of the twentieth century, and we lost that.

We tend to focus on the loss of manufacturing jobs as the reason behind the decline of the middle class, and therefore the decline of many of our cities. Surely that has had a significant impact. But perhaps we should shift our focus on the decline of policy supports that once existed at the federal level that enabled our middle class to grow. There was once a rich mix of tax policies, housing programs and labor protections that supported the middle class incomes that American corporations and businesses were paying. Since the late 1970's there's been a slow, yet steady erosion of those policy supports - and coincidentally, our middle class decline has occurred over the same period.

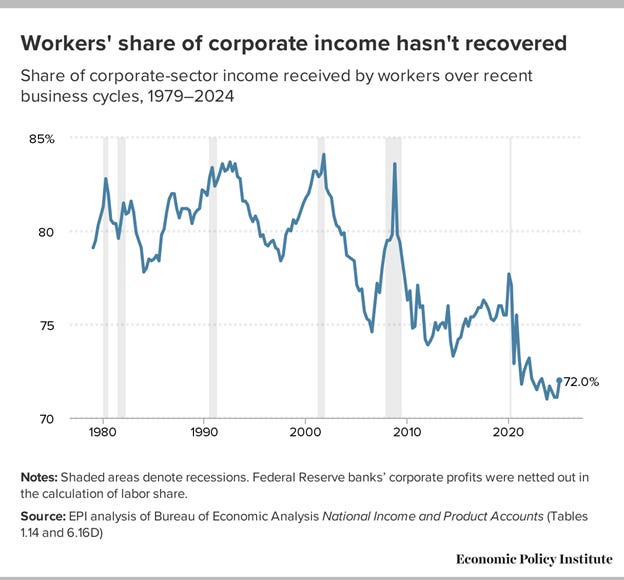

Here's another way of looking at it. Except for the 18-month Covid pandemic spike in unemployment between March 2020 and September 2021, the U.S. national unemployment rate has been consistently at five percent or lower since September 2015. Despite that, wage increases have consistently failed to keep pace with the employment gains since the end of the Great Recession, causing broader economic uncertainty that belies the low unemployment rate. Wage growth has been concentrated at the high end of the wage spectrum; the most wage growth was made by the top 10 percent of wage earners. This chart from the Economic Policy Institute, further illustrates how worker’s share of corporate income has diminished:

The truth is, people are working, but they're not working in jobs that are considered "middle class jobs" as much anymore.

We tend to focus on particular job types when we refer to the middle class. Manufacturing jobs, for example, are middle class jobs; food service and hospitality jobs are not. Perhaps the first step toward rebuilding the middle class is to change our definition of it.

At the end of the nineteenth century, agriculture jobs were considered middle class jobs, and early manufacturing jobs were not. However, as jobs shifted from one industry sector to another, manufacturing jobs became middle class jobs. Wages and incomes adjusted to accommodate the change in the economy, and public policy, particularly at the federal level, evolved to support the change. Over the last 40-50 years, manufacturing jobs have declined, and service jobs have increased, in perhaps the same way that agriculture jobs declined and manufacturing jobs increased in the 1890's. But the wage adjustment that occurred then hasn't - isn't - happening now.

We can't completely blame cities for their focus on the upper middle class. We have a government that hasn’t supported the middle class for several decades now. Even worse, we have a government that has not anticipated the evolution of work, of workers, and the future composition of the middle class for decades, either.

The last time the nation supported the middle class, our suburban areas benefitted the most, through policies like insured home mortgages and interstate highway development. Sixty years ago people were saying cities didn't support the middle class, yet the truth was that they simply weren't well-suited to receive the benefits bestowed on suburban areas. In the intervening half century cities adapted, found a way to compete for the socio-economic class that was indeed growing, and are getting hammered for growing inequality.

This is a solvable problem.

We need a national policy to turn the service jobs that make up the bulk of our workforce today into middle class jobs. The level of skill it once took to work on an industrial assembly line is not that different than it takes to work in today's service jobs, yet the pay is entirely different. Cities, the home of a critical mass of service workers, should be at the forefront of federal policy advocacy for a new middle class definition and support. Yes, cities would stand to benefit most directly from those middle class policy changes. But suburban areas would stand to gain as well, as they are increasingly threatened by middle class erosion. They need this too.

Reinvention begins with reimagination.

The welfare of service workers is not a problem that is best solved through regional approaches; that is, we supply affordable housing within a region and provide public transportation for commuting all over the region. The policy win would be housing access for service workers within the neighborhoods where they work. Proximity is the most accessible urban arrangement and the cheapest. One of the greatest burdens borne by service workers is irregular work scheduling. The flexibility of the car is what most service workers rely on to keep to those schedules. We should offer them the option of proximity as a cost-effective alternative.