Planning and the Public Realm, the Way It Used to Be

Maybe giving up control of the public realm was more significant than embracing land use restrictions via zoning.

If you’ve been reading my work for some time, you might know that if I’m a big fan of streetcar suburbs. In my opinion they represent the best planning that’s ever occurred in the U.S., incorporating walkable access, transit, neighborhood, institutional and commercial nodes, and a mix of housing types – at transit-supportive densities – that created a golden age for American cities.

Some time ago I came across a really interesting book that resulted from a Chicago competition more than a century ago. In 1912, the City Club of Chicago called for a competition to come up with innovative residential land development design ideas for the outskirts of the city, based on the size of the general development slice of the time, the quarter-section (160 acres). The competition is a little-known event even to architects, urban designers and planners, possibly because it came on the heels of the Commercial Club of Chicago's 1909 Burnham Plan. Whether the City Club released the competition as an outgrowth of the Plan, or a practical and competing alternative to it, I don't know.

The competition was recounted in a book published by the City Club four years later, compiled by Chicago landscape architect Alfred B. Yeomans. The book, City Residential Development: Studies in Planning, documented that this was the challenge set forth to the competitors:

"Within the built-up portions of the city changes in the street plan and the creation of open spaces are enormously expansive and difficult. On the other hand, every large city includes within its limits large areas of unimproved or partially improved land where the city planner, real estate operator, and others may work practically unhampered by the ideas or lack of ideas by their predecessors.

There is increasing evidence of a tendency in this country to take advantage of these opportunities to intelligently direct and control the growth of cities. The purely mechanical extension of existing street systems is giving way to scientific methods of land development based on careful study of the probable economic, social and esthetic (sic) needs of the prospective inhabitants."

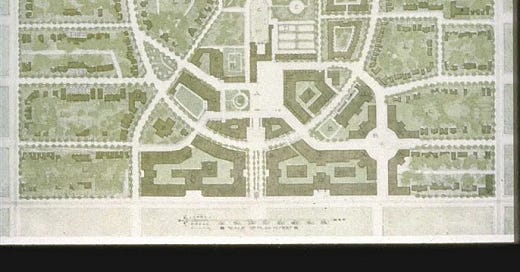

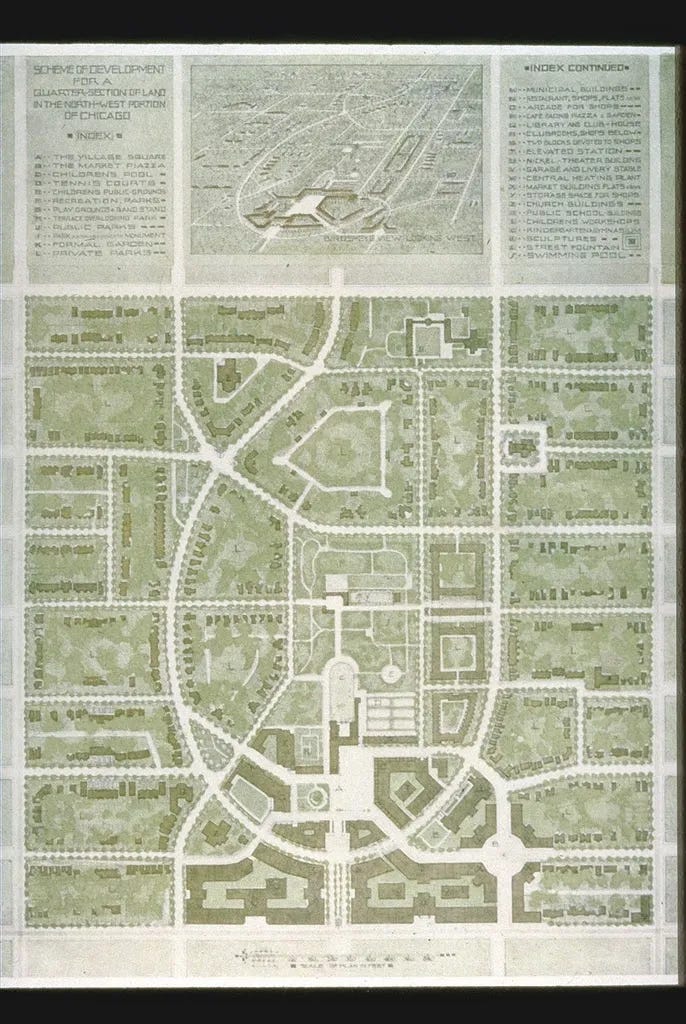

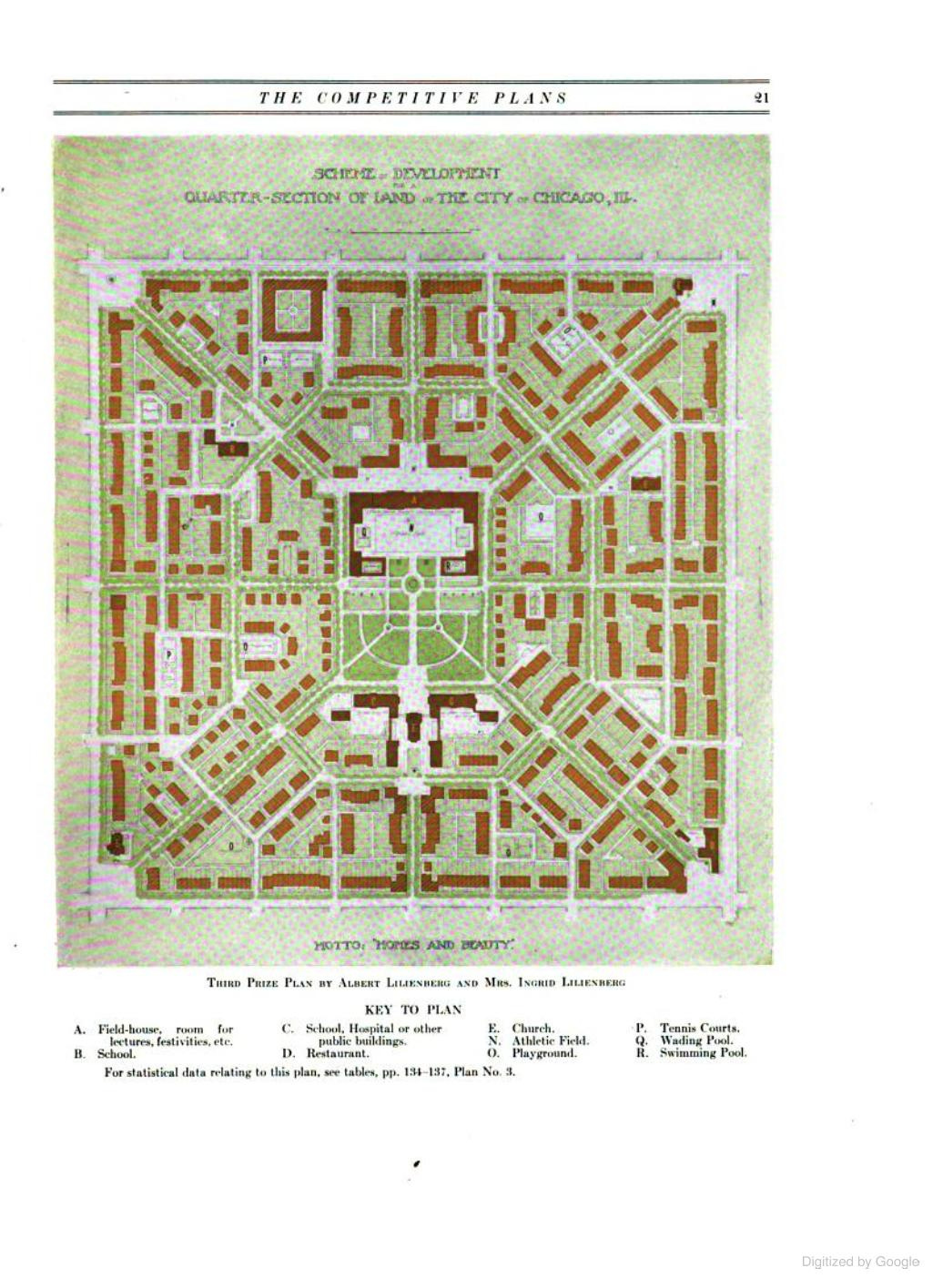

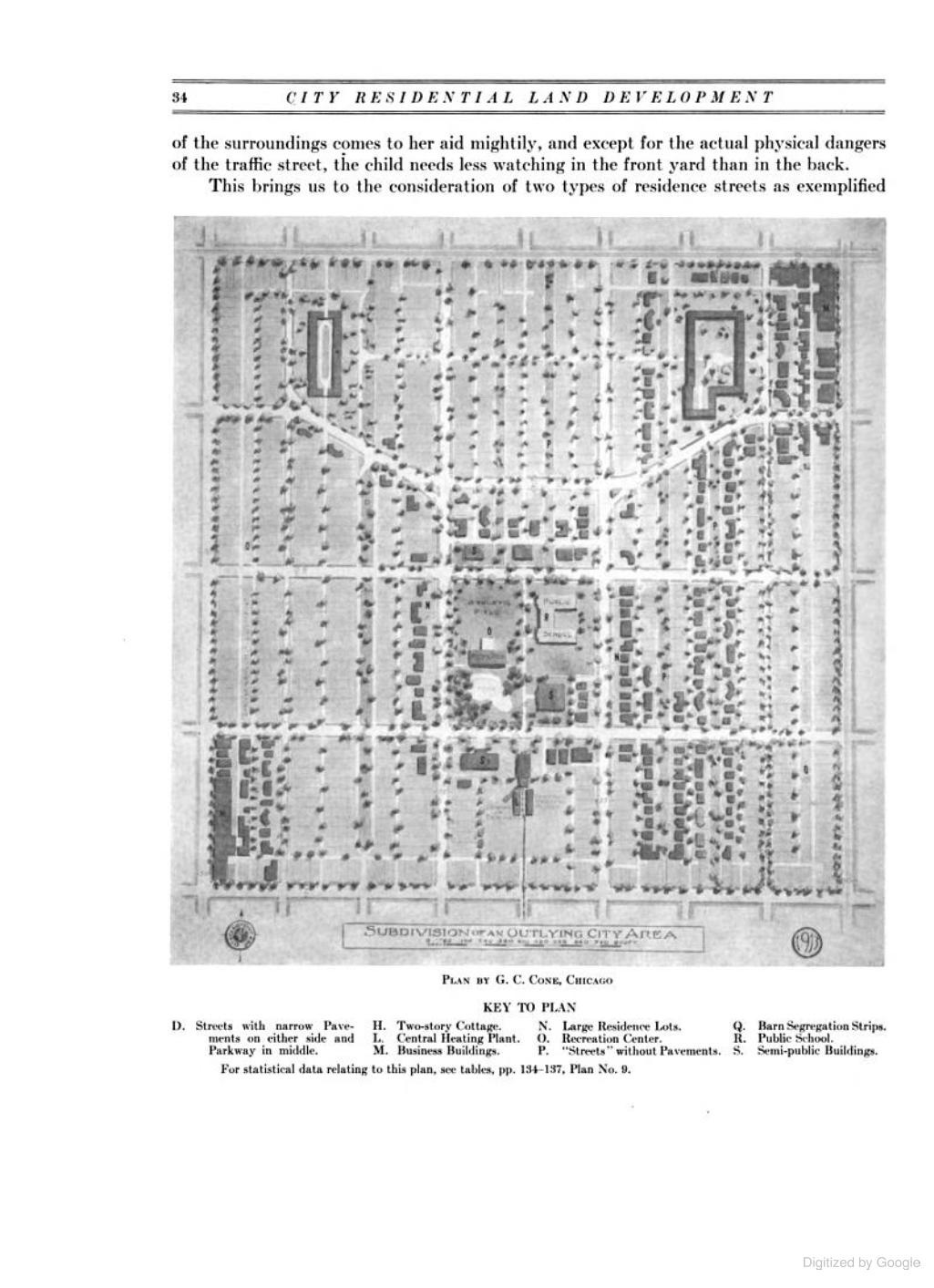

The competition set standards for development (commercial areas, schools, churches, open space and other uses should be accounted for, as well as residential uses), as well as a recommended density (suitable for no more than 1,280 families, or a gross of 8 du/ac). In all some 33 plans were submitted from around the country, including a non-competitive submission from Frank Lloyd Wright. The winning submission came from architect Wilhelm Bernhard of Chicago, who submitted a graceful plan of a dense, walkable and self-contained community with a mix of uses based on a gentle variation of a street grid design. Check it out above. It would be the envy of New Urbanists everywhere, and I like it.

Yet in many respects this competition itself represented the end of one kind of city planning, and the emergence of another.

The seeds of the future direction of American land development are in the challenge to the competitors. Rather than pursuing the rote extension of the street system and pattern, the competition's judges wanted "scientific methods" of land development. What was lost in that transition was something taken for granted by cities at the time -- the presumed primacy of control of the public realm by cities. Cities have been struggling to regain that control ever since.

Take a look at the submissions in the book. The submissions are very different, from grid-based to geometric patterns. Here are a couple of grid-based, densely developed plans:

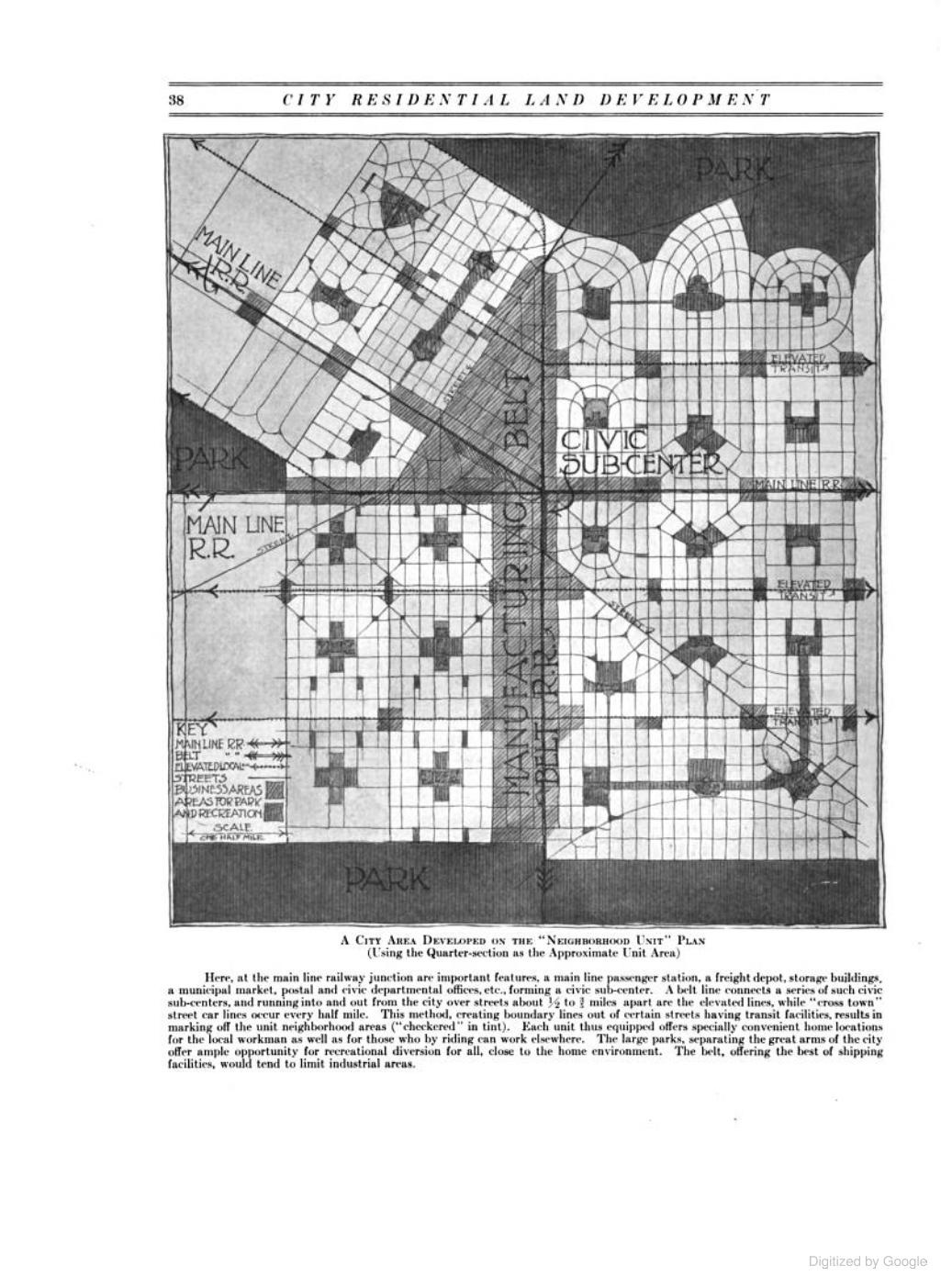

And here are some large-lot, curvilinear and geometrically designed plans that anticipated the future of American suburbia:

But the assumption for nearly all was that they would fit within an established framework. Their designs would be connected to the grid system just beyond it. The city, having the final say, would establish a consistent framework or template upon which the city would be built, and not that developers would create piecemeal, disconnected parts that have little relation to each other.

Ever since, planners around the country -- myself included -- have deluded themselves in the development review process, evaluating subdivisions with only passing thought to their connectivity and impact, especially if the proposed development enjoys strong political support or seeks to attract a favored demographic to your town.

Once upon a time, city planners established a framework for the private market to flourish. Today, the private market sets the tone, and we try to backhandedly set the framework.

No wonder our profession struggles with an identity crisis.

I am somewhat unclear on what the shift is you are documenting here vis-a-vis city planners. In my mind, the 19th century is the period of time that cities shifted into being planned, and the mid 20th century that time where city planners were most powerful.

Yet, it is that same period that sowed our cities destruction. I don’t feel that the problem was a loss of control over planning, the triumph of the private over the public, but precisely the opposite. Cities should be planned _much less_ than they are. I would think you agree, so that is where I feel I am missing your point.