Thoughts About Reimaging Suburbs

Maybe our nation's housing crisis is because of a lack of imagination, not a lack of supply.

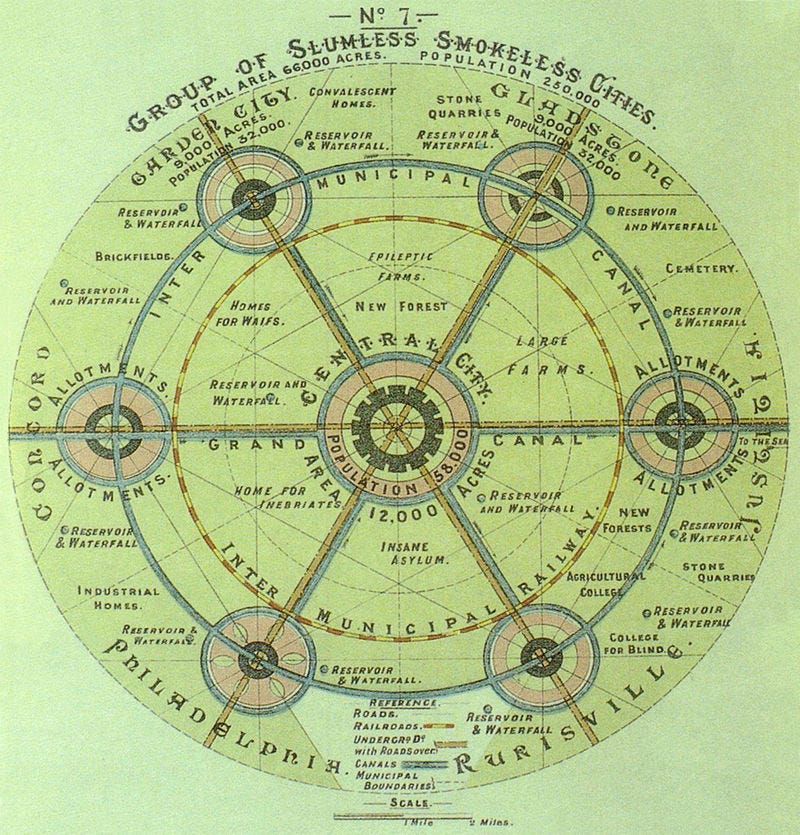

Ebenezer Howard’s original Garden City concept, published in 1902. Source: wikipedia.org

When I wrote about streetcar suburbs a couple weeks ago, I described them as an excellent design model for increasing residential density in today’s suburban landscape. Some contemporary urbanists might push back against the streetcar suburb model for suburban retrofitting, arguing that I am proposing switching from one suburban framework to another, when we should be creating more explicitly urban frameworks nationwide. However, I think it should be noted that the streetcar suburb was initially designed as a modest, transit-oriented adaptation for urban development. Implementing more of this adaptable design (which can be successful with or without transit) can be the essential step needed to opening up housing opportunities for more people, relatively quickly. A look into how they came into being, and how they developed in their early years, can give us some insight into how they can play a critical role today. Follow their development, and you’ll notice the evolution of the American suburb taking place – and ironically, how its early roots can help cities.

Suburbs have been around as long as there’s been cities. Put another way, less-dense living space options have always been attractive to a segment of people living in more-dense environments. People lived near or adjacent to walled castles or forts for protection and access to goods; they sought to bridge the distance between the people who bought their produce from the fields where they were grown. But it was in the mid-19th century, with the rise of the railroad, that what people today identify as “suburb” was created.

The affluent understood early on the benefit of quieter and controlled living, and established places like West Orange, NJ’s Llewellyn Park, 12 miles west of Manhattan. It became the nation’s first gated community in 1853. But railroads expanded the commuting reach of the city. It didn’t take long for wealthy people to gravitate toward quieter areas with a more rural atmosphere. Soon, Philadelphia’s Main Line suburbs were constructed, and Riverside, IL, outside of Chicago, became the nation’s first planned community in 1869.

Ebenezer Howard, the pioneering British urban planner and founder of the Garden City movement, sought to build on the principles of early suburbs. Howard imagined cities where people lived and worked harmoniously with nature. And (a parenthetical note: this is my guess here, because he often does not get credit for this), he sought to expand this style of living beyond just the affluent classes that set the pattern.

Howard published To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform in 1898, which was renamed Garden Cities of To-Morrow in 1902. Howard used the success of the book as a springboard to develop actual garden cities in Britain, beginning with Letchworth Garden City in 1903, and Welwyn Garden City in 1920.

Back to my parenthetical note above. Ever since I first came across the work of Ebenezer Howard in college, I immediately made the connection I saw him making to improving the quality of life of city residents by bringing the best aspects of city living (job opportunities, higher wages, more commercial and social amenities) with the best of country living (fresh air, spaciousness). But I think there’s something telling in the renaming of his book four years after its original publication. Perhaps Howard, or his publisher, or his investors in developing garden cities, realized that the social reform goals that Howard desired from garden cities weren’t quite as marketable as more land and space. That’s unfortunate, because I believe he was onto something. Reducing his model to one of just more spacious living directly leads to the problems we have with suburbs today – auto-dependent sprawl, hyper-individualistic behavior, social disconnectedness, and more.

Another thing that was lost in the change? The importance of transit in connecting urban and rural areas. Every diagram that Howard made of the concept included railroads or streetcars that linked satellite cities with each other, and the satellite cities with the central city. He understood the importance of that connection.

At any rate, I see five distinct iterations of the railroad or streetcar suburb that arose in the late 19th century, later influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City movement. Here they are below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Corner Side Yard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.