Unresolved

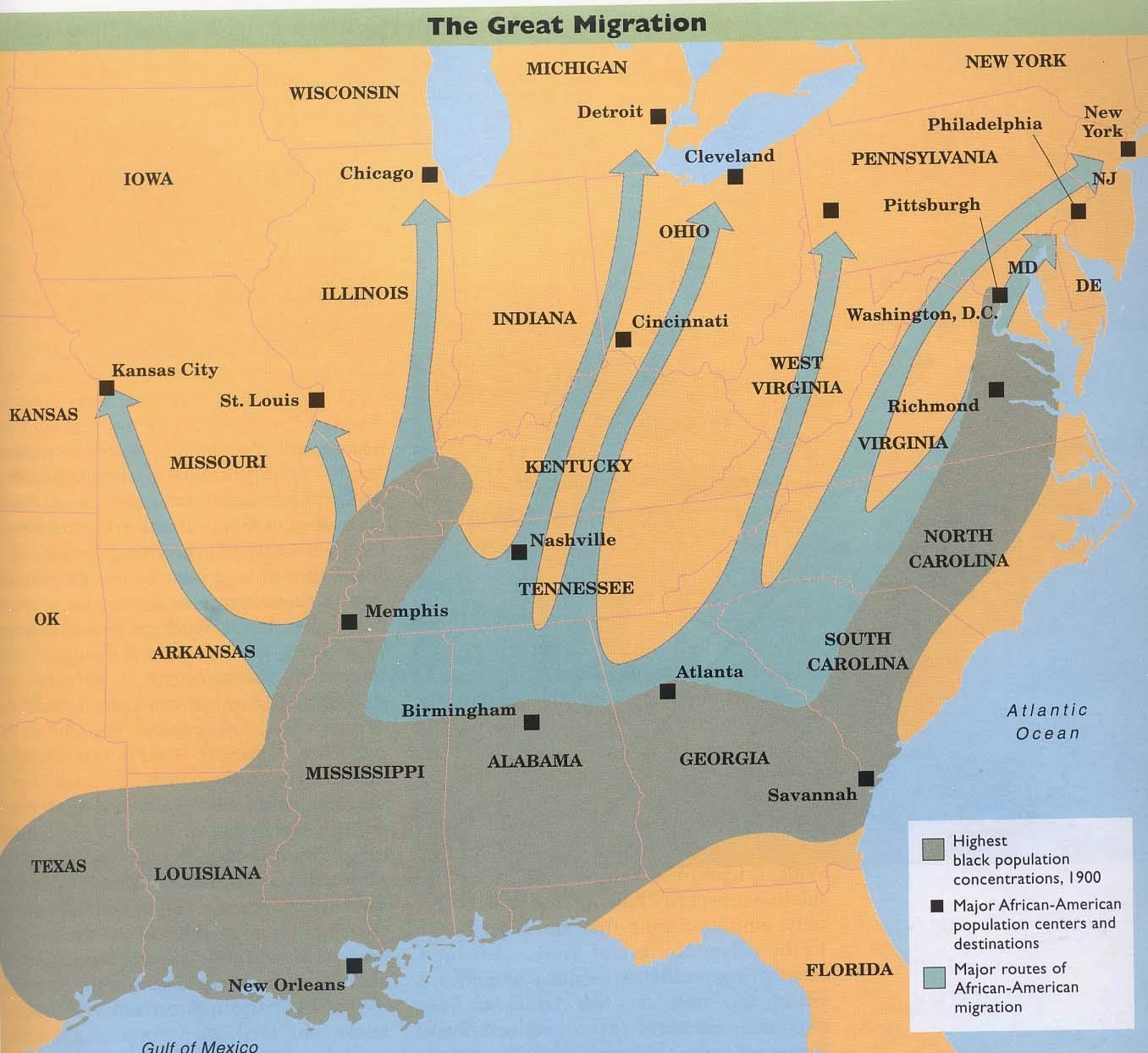

A graphic explanation of the Great Migration. Source: social.rollins.edu

It may seem a stretch to connect the grand jury decision and subsequent protests in Ferguson, MO with broader trends in American urbanism like gentrification or growing suburban diversity, and their impact on cities. But in the absence of any definitive and explicit urban policy in the U.S., what's happening in Ferguson and the larger St. Louis area, and by extension America's Rust Belt, is vitally important.

It's becoming clearer that America's Rust Belt is emerging as the flashpoint for the intersection of race and urbanism in America. At various points in the last few years, Chicago (crime and inequality), Detroit (crime, corruption, bankruptcy), and Ferguson/St. Louis (the Michael Brown shooting and protests) have been in the news for having eruptions on this fault line. Many other Rust Belt cities, like Cleveland, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Louisville, are well known for problematic racial legacies and are often regarded as being simmering pots that are one troubling event from a Ferguson-like eruption. The recent police shooting and killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland may represent yet another opening on this front.

How is this happening? Why is this happening now? Why, after all the progress made from the Civil Rights Movement in the '60s, is a new fault line emerging? While American society "solved" the problem of explicit, race-based laws in the Jim Crow South, it has yet to fully deal with the far more complex and ostensibly "race-neutral" policies that emerged in Rust Belt cities more than 100 years ago, and still define how we interact with each other in Rust Belt cities today. What was first invented and developed in Rust Belt cities was exported throughout the nation. Let me demonstrate and explain.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates so artfully and eloquently detailed in his essay, The Case for Reparations, this starts with the Great Migration. Conditions for African-Americans in the Jim Crow South during the first two-thirds of the 20th century were often horrific. Coates' essay goes beyond what we typically know about the era -- the lack of voting rights, separate facilities on all fronts, lynchings -- to expose the daily indignities that reinforced black plunder and second-class citizenship. Clyde Ross, a man born in Mississippi in 1923 who later moved north to Chicago, was interviewed by Coates and spoke of his childhood:

As sharecroppers, the Ross family saw their wages treated as the landlord’s slush fund. Landowners were supposed to split the profits from the cotton fields with sharecroppers. But bales would often disappear during the count, or the split might be altered on a whim. If cotton was selling for 50 cents a pound, the Ross family might get 15 cents, or only five. One year Ross’s mother promised to buy him a $7 suit for a summer program at their church. She ordered the suit by mail. But that year Ross’s family was paid only five cents a pound for cotton. The mailman arrived with the suit. The Rosses could not pay. The suit was sent back. Clyde Ross did not go to the church program.

Slights like this defined Southern society perhaps even more than the Jim Crow laws themselves, and that sparked the start of the Great Migration. Some 6 million African-Americans moved from the South to the North between 1910 and 1970. And as Coates puts it:

The black pilgrims did not journey north simply seeking better wages and work, or bright lights and big adventures. They were fleeing the acquisitive warlords of the South. They were seeking the protection of the law.

But Northern cities were hardly the utopia for blacks that many anticipated. Few Northeastern and Midwestern cities had in place the race-explicit laws that defined the Jim Crow South (the notable exceptions being cities like Indianapolis, Louisville, Cincinnati and St. Louis, which straddle the north/south line), but by the start of the 20th century nearly all were well-versed in exclusion. Most Northern cities had instituted measures designed to limit the physical movement of Irish, German, Italian, Jewish and Polish immigrants moving into large cities, and it did not take much to consider how the same policies could be reworked to enact the same toward blacks. That means that almost immediately upon their move north, blacks found a new set of rules and policies that defined the extent of their existence. Restrictive covenants limited their ability to move. Redlining took away access to credit for mortgages or establishing businesses. Exclusionary zoning created artificial barriers and limits to housing supply. Blockbusting techniques ensured that if blacks were to create a neighborhood breach, real estate agents would profit from selling fear to homeowners. School integration efforts were fought with extreme prejudice. Tough police measures and sentencing laws tried to stop crime from spreading, but were largely successful only in creating a criminal underclass.

There is perhaps no clearer explanation of the differences between Northern and Southern discrimination practices than one offered by comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory more than 50 years ago. I'm paraphrasing here, but essentially he said: "the difference between racism in the South and North? In the South, they (whites) don't care how close you live to them, just don't get too big. In the North, they don't care how big you get, just don't live too close."

Northern discrimination policies have kept African-Americans from living too close to whites, and this exclusion, even when not explicitly done so, has been baked into American urban development policy for the last century. Indeed, it has become American urban development policy.

By the end of World War II, it was clear that there were two fronts in the fight for civil rights -- the race-explicit policies of the Jim Crow South, and the "race-neutral" policies of the North. At best, one can say the Civil Rights Movement conquered Jim Crow, but only fought Northern discrimination practices to a stalemate. The divide persists.

The destruction of Jim Crow did not mean the destruction of American racism. It meant the end of one kind of racist structure, and its replacement with a new one that had been tested and implemented in the Rust Belt. Southern cities have seen some measure of progress for African-Americans as Jim Crow practices have faded into our distant memory. But that progress comes with a low ceiling; Southern cities now have many of the structural, "race-neutral" practices that the North perfected. As for the Rust Belt? Little progress has been made by African-Americans over the last 50-60 years. However, recent trends, generally applauded by urbanists, are putting Rust Belt cities front and center in a new civil rights debate.

The first trend? The return to cities by young adults that began in the '90s and continues to accelerate to this day. It's been at the core of the revitalization of scores of cities across the country, from New York to Portland, and Minneapolis to Miami. For decades our national preference for living and working was the suburb; now it appears our nation could be witnessing an enduring shift in city/suburb preference, or at least the establishment of a new equilibrium.

The second trend? The growing diversification of our suburbs. Minorities of all types are accelerating their move into the previously homogeneous suburbs. Hispanics, Asians as well as African-Americans and others are pursuing the American Dream that generations of Americans before them pursued. They want what so many before them wanted -- spacious homes, green lawns, safe neighborhoods, excellent schools.

This is creating a really interesting dynamic, and a tension that is perhaps strongest in Rust Belt metros. The migratory shift in both directions is an inverse of what's occurred in metros for the last 100 years. Since the advent of the Great Migration, white residents in Rust Belt cities have steadily moved outward, fueling suburban growth, as blacks entered cities. While "white flight" may not have been the primary driver of suburban growth, it was often part of the decision-making process, especially when property values were of greatest concern. Today, whites moving into cities and minorities moving into suburbs represents a fundamental pattern disruption to our de facto urban development policy, and we're not prepared to deal with its ramifications.

Ferguson and St. Louis represent one Rust Belt response to this tension. Where they can, suburban municipalities can adopt a strong, protect-and-preserve mentality, seeking to maintain housing values and protect local businesses. Unfortunately, the downside is that those doing the protecting define the "threat", and doing so dehumanizes those on the other side of the divide.

Chicago and Detroit represent another Rust Belt response. We can create a bifurcated city (Chicago) in which an affluent slice of the city is buffered from the more distressed parts. If done well, inhabitants of the affluent portions of the city can effectively "rub out" any nuanced knowledge of any part of the city apart from where they live. Or we can even create an entirely bifurcated metro (Detroit), whereby an entire city gets the same shunned treatment.

Cities like Indianapolis and Milwaukee may represent yet another Rust Belt response. Believing that their cities/metros hold none of the tensions apparent in St. Louis, Chicago or Detroit, they elect to... do nothing. They, of course, do have the same tensions, just not the requisite spark to catalyze them. City leaders in both cities would be wise to ask Cincinnati leaders about their experience and about appropriate actions.

Whatever the chosen Rust Belt response, the nation awaits a resolution on a Rust Belt creation. The Rust Belt produced and exported far more than coal, cars, steel, chemicals and processed foods. The Rust Belt also produced and exported its brand of so-called "race-neutral" urban policy to the rest of the nation. It's up to the Rust Belt to lead us to the next level.