Unresolved, Con't. -- The Tools of Containment

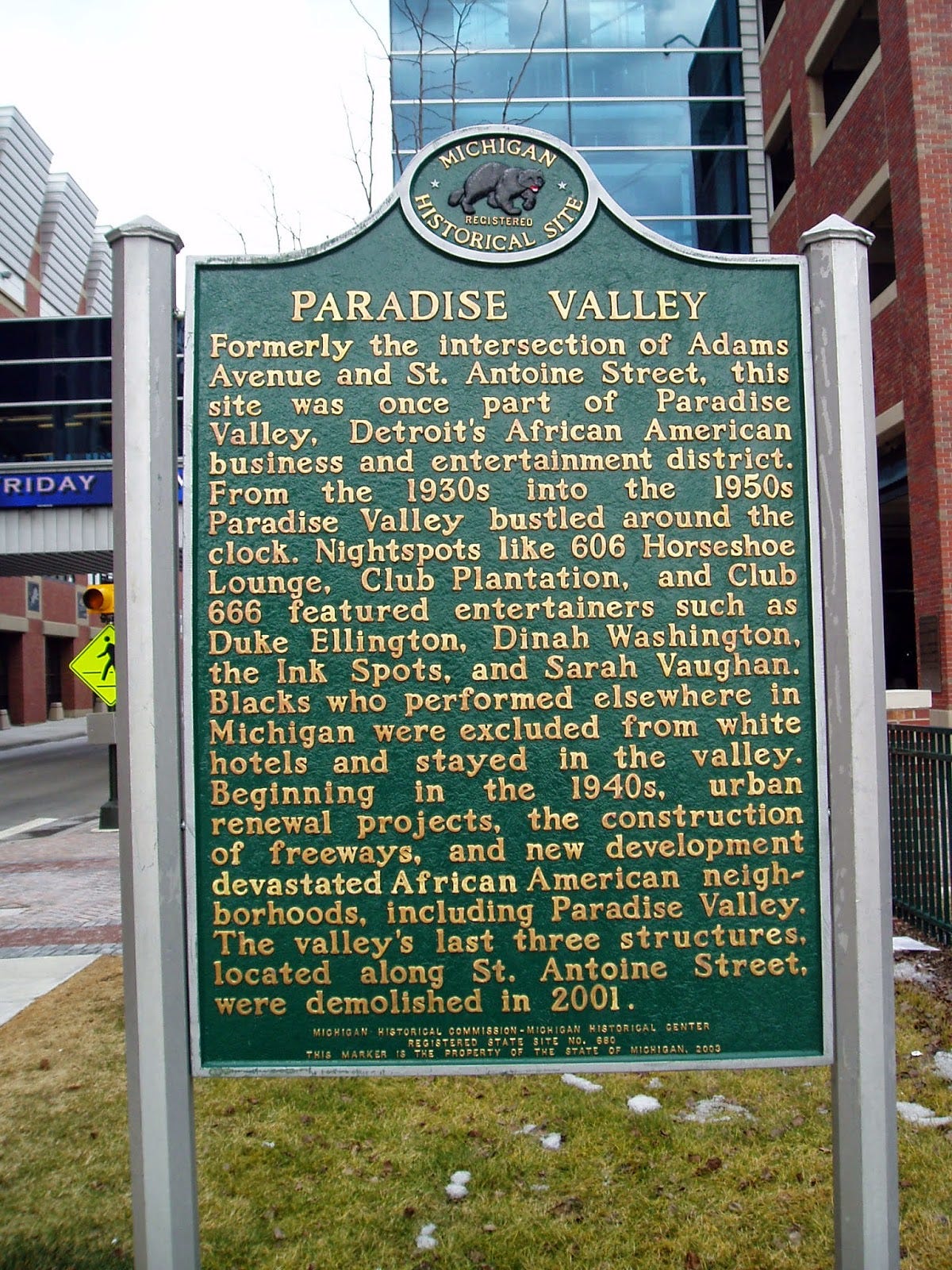

Historic marker for the now-gone Paradise Valley neighborhood in Detroit. Source: detroit1701.org

After reflecting on my post from a couple days ago, I realized there are many people who are unclear on the 20th and 21st century tactics that have been utilized to contain and exclude African-Americans since their migration to Northern cities began more th…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Corner Side Yard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.