We Don't Need Policy When Practice Will Do

Maybe redlining wasn't the "aha!" policy that explains today's troubling racial inequality.

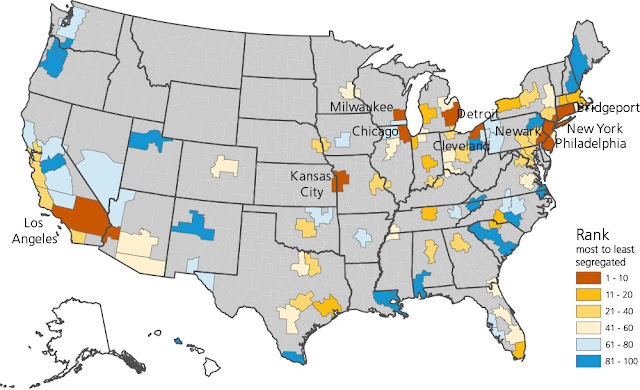

A map showing Black and Latino segregation in the nation’s 100 largest metro areas in 2010. Source: https://metroplanning.org/the-cost-of-segregation-2/

I’ve been a big fan of Alan Mallach of the Center for Community Progress for years. I first met him at a Cleveland Fed conference in Cincinnati in 2017, and later interviewed him at the University of Chi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Corner Side Yard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.