The Abundance Movement And The Inner City

Housing devaluation can become an even bigger problem.

Aerial view of Bloomfield Hills, MI, in metro Detroit’s Oakland County. Source: landsearch.com

Here’s a story for you. Some ten years ago I came up with what I thought was a good, if poorly named urban policy idea: the “gentrification management” program. The idea was simple. In the 2010s cities were regaining interest throughout the country as young adults settled in. I saw this as a two-fold opportunity. On one hand, the pre-WWII neighborhood inventory and infrastructure that sparked the 2010s urban revitalization was limited, and this was a chance to finally add to it. On the other, I saw neighborhoods that already had that inventory but were being passed over, yet still in need of the investment that comes with revitalization. Finding a way, I thought, to bridge fears of gentrification and displacement with principled and equitable redevelopment would make for better cities.

Bottom line, the idea flopped. The urbanists of the time saw enough low-hanging fruit in zoning reform to pursue; they argued that loosening the reins on single-family zoning would lead to new housing development and eventually push prices down. I argued that there were many challenging but similarly developed city neighborhoods that could fit the bill but remained ignored. It became clear to me that many emerging YIMBYists wanted more housing in the hottest neighborhoods, and not necessarily more neighborhoods that could be made more viable and attractive.

I left the idea alone, yet never really abandoned it. Perhaps the idea was poorly conceived, overly optimistic, or simply stuck with a bad name. Whatever. I’ve written a lot of words over the last month about “garlic knot” metros or distressed neighborhoods, and I remain convinced that such neighborhoods are a part of the solution for improving housing affordability, and not the problem that we choose to avoid.

We’ve now come to a point where the YIMBY movement has expanded past its housing affordability roots to something broader – the abundance movement. Over the last ten years YIMBYs have been successful at getting legislative wins at the local and state levels across the country and getting new housing units built as a result. YIMBYs are pointing to decreased sale prices and rents in many metros. It’s to be expected that some would view YIMBYism as something that could be scalable as a national policy platform.

Back in April I wrote about the movement spearheaded by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book. I wrote about how the YIMBY movement created a new way in which to view America’s inability to produce:

“Whether it’s affordable housing, or infrastructure, or addressing climate change, the regulatory structure we’ve established since the 1970’s has so many checks and balances that the structure opens projects up to detailed scrutiny, substantially increases project costs, and ultimately disincentivizes builders to build. America hasn’t been able to get what it needs today because the regulatory environment from an earlier era expressly prevents it.”

As well as my critique:

The simplest way to describe my reservations might be that YIMBYism is a “good for thee, but not for me” sort of movement in my mind, in that I still see huge swaths of Rust Belt metro areas that are undervalued relative to coastal metros and suffer from a lack of demand rather than real demand intensity. Sure, there are spots within the Midwest’s biggest metros that are as expensive as coastal cities, with the same kinds of demand pressures. But Midwest metros aren’t as uniformly expensive as coastal metros. They’re usually offset by less expensive (and yes, less desirable) communities and neighborhoods that have borne the brunt of deindustrialization over the decades. That’s a problem for many Rust Belt metros – and one without a YIMBY solution.

We’ve seen this movie before, and that’s why I think that Conor Dougherty’s New York Times article “Why America Should Sprawl”, which also came out in April when I wrote my initial critique, is so concerning. It represents what could be considered the next phase of the YIMBY movement, as well as a foundational piece of the emerging abundance movement.

I think it leads directly to an even more unequal cities, and more unequal society, than we have today.

Back in May when I did an earlier response to Dougherty’s article I brought this point up:

“I’ve had a theory for several years that the city/suburb divide in Midwestern metros is the widest such divide in the nation, and contributed to their subsequent decline. My theory: deindustrialization in the Midwest began at exactly the same time that post-WWII suburbanization took off, and millions of Black people from the South moved north in search of jobs in a market that was becoming much more competitive. Combine that with the social upheaval of the 1960s and 1970s, and the trajectory of Midwestern cities was forever altered.

See, even though Midwestern metros grew at a substantially slower pace after 1950, with population losses concentrated in their central cities, they continued to add millions of homes on the suburban edges in numbers that surpassed the actual demand for new housing. The chief migratory movements in Midwestern metros from 1970 until today have been 1) city residents moving to the suburbs; 2) inner suburban residents moving to outer suburbs, and; 3) metro residents moving entirely out of the metro. Home builders reacted to the demand for suburban homes and continued to build them. But without any in-migration taking place in Midwestern cities, housing value within them evaporated. In effect, population loss in central cities pushed the price floor downward. That made continued suburban expansion more affordable to construct.

That’s how Rust Belt cities became affordable.”

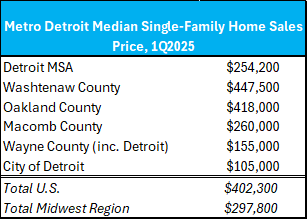

If you’ve ever heard the adage “if you have one hand in the oven and another in the freezer, on average your hands are fine,” that’s one way to explain housing values in Rust Belt cities. Let me explain. According to a quarterly report released by the National Association of Realtors in May, the national median sales price of existing single-family homes nationwide was $402,300 in the first quarter of 2025. Of course, there’s a great amount of variability in the numbers when you look deeper: metros in the West had the most expensive median at $626,000, and Northeastern metros followed at $482,700. Southern metros were third at $361,800, while Midwestern metros were last at $297,800.

In the post I referred to above, I explain how over the last 50-60 years Chicago and Detroit continued to build homes throughout their metros at rates far beyond what their population growth would indicate. The growth in housing numbers generally occurred in the suburban areas of both metros. As a result home prices did moderate in Rust Belt suburban areas compared to the suburbs of other metros. Yet a clear argument could be made that the moderation came as a result of the devaluation of housing in inner city neighborhoods.

Detroit’s probably the best metro area example to demonstrate my point because neighborhood distress in metro Detroit is particularly contained within the Detroit city limits. Check out this chart:

Let me make one thing clear from the outset: as a region metro Detroit has been stagnant in terms of population growth for a half-century. Between 1970 and 2020 the U.S. gained 63% in population, while metro Detroit lost 0.9%. That fact alone can account for the remarkable housing affordability of the Detroit area. Indeed, of the 54 metro areas with more than one million residents, Detroit ranks 50th in median existing single-family home sales (ahead of Buffalo, Rochester, NY, Pittsburgh and Cleveland).

The table above suggests that much of the region’s suburban areas have values that are near, even above, the national median, while Detroit itself and its host county, Wayne, are substantially lower. In fact, perhaps a case can be made that there’s housing price suppression in Detroit and Wayne County that keeps prices low there, and higher in the suburban counties.

I understand the frustration people have with housing affordability. But does it apply to every metro? Is it possible to extend the logic too far?

It's really too bad that your idea wasn't widely embraced, -it would help so many cities become more livable places. Unfortunately, there is the whole incentive issue. Are developers, planners and politicians actually incentivized to maximize equitable developement in urban areas to improve quality of life for as many as posible? Unfortunately it seems the amswer is no. On another note, the whole one hand in the oven the other in the freezer anology is also spot on, and gave me a good chuckle!