The Differences Between Constrained And Expansive Cities

It's always going to be an apples-to-oranges comparison.

Pittsburgh’s had the same municipal land area, about 55 square miles, since 1955. At that time Oklahoma City covered the same amount of land. Today OKC is more than 10 times physically larger than it was 71 years ago. Source: gettyimages.com

First off, I’m going to pivot away from the promised part 2 of the Cities Within Cities piece I wrote Wednesday. I ran into some snags, so I’ll finish it when I can. Today, I’d like to respond to a comment.

Ben Schulman, a CSY subscriber and reader, reacted to my piece by responding with this below:

Love this. Reminds me of the work that a colleague and I did to standardize the size of the American city to illustrate the illusory nature and perception of population as a metric of civic success and health:

https://beltmag.com/population-aint-nothing-number-standardizing-size-great-american-city/

I want to thank Ben for his comment and link. I’ll also note that I quote somewhat liberally from the article, and that I reformatted tables from the article for use here.

The article, published nearly 12 years ago, made some amazing points about how we view cities. From the article:

“While the health of cities is often discussed in terms of population, what’s often lost in the discussion, at least outside of certain wonky urbanist circles, is the size of cities in geographic terms. (Unless that city is Detroit, whose 139 square miles seem to be lambasted at times as one of the central causes for the city’s steady decline.) Putting density and urban design aside, simply taking a quick look at the square mileage of American cities reveals a wide disparity, from the 757.7 square miles of Jacksonville, FL to the 14.79 square miles of Jersey City, NJ.

Although cities are often judged prima facie, not to mention showered with congressional dollars via census results, based on population figures, perhaps a straight reading of the numbers isn’t a good barometer of the merits or demerits of a place given the wild variances in the geographic size of cities.

Cities are arbitrarily constructed entities with culturally loaded boundaries. So what would happen if every city shared the same geographic borders? Would population numbers reflect different realities? Would the perceptions of places change, defining which cities are viewed as declining or prospering?”

Schulman and colleague Xiaoran Li then took on an interesting GIS-based experiment. Using 2010 Census data, they calculated the average square mileage of the 10 largest cities in the U.S. at the time. They found that the average of the top ten was 355 square miles. Houston, at that time a mere 600 square miles, was the largest in land area of the top ten cities, while Philadelphia was the smallest at 134 square miles.

What’s interesting, but must be made clear, is that older cities in the Northeast and Midwest, like New York City, Philadelphia and Chicago, have had their boundaries set for a century or more. However, younger, more recently developed cities like Houston, Phoenix and San Antonio (and also Los Angeles, which is nearly as old as the Northeast and Midwest cities, but, unlike them, still has been able to gobble up land) just kept getting physically larger.

That’s an advantage for younger cities that few people consider.

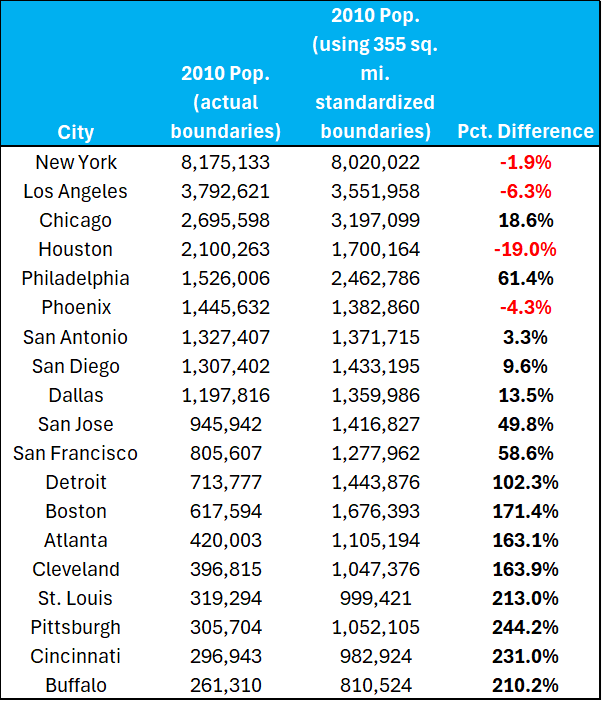

They then used GIS software to estimate population for cities using the standardized 355 square mile area. As you might guess, expansive cities that were already above the 355 square mile threshold shrank in size, while those below it grew substantially. Constrained cities added population, while expansive cities shrank. Consider this table of estimated population at the 355 square mile standard, replicated by yours truly to arrive at percentage changes:

One point Schulman and Li noted was that expanded territory didn’t expand population in every case, nor did shrunken territory always lead to shrunken population. In fact, New York’s land area increased by more than 50 square miles but its population at the standardized 355 square mile threshold dropped, while San Antonio’s land area shrank by more than 100 square miles but its population rose. They attribute that to “quirks of geography and the presence of independent enclaves.” But I think it can also be explained by steep density gradients in metros like New York (it’s far more dense in Manhattan than in Westchester County), and the possibility that San Antonio annexed land that did not develop as expected, and other areas not annexed by the city did.

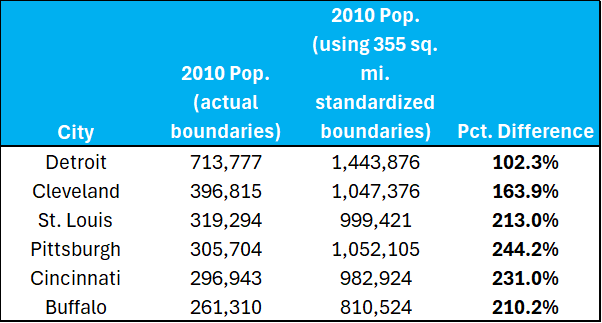

But the big takeaway to me is that Schulman and Li show that this impact is greatest on the cities of the Rust Belt. Let’s focus on them in the next table:

In each case the 355 square mile standard means double the population for all cities; four cities (St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Buffalo) would have triple the population.

A couple of conclusions can be made from this exercise. One, made by Schulman and Li, is that larger sizes would done a lot to get rid of the decline narratives that set in for each of them. All of the above cities are known for the steepest population declines seen in the U.S. since the mid-20th century. A Pittsburgh that had 676,000 people in 1950 but over one million in 2010, for example, might not be viewed as one of deindustrialization’s casualties. I’ve argued the same point.

The other conclusion? When I see 2-3 times the population because of expanded boundaries, I see 2-3 times the tax base available to local government. The ability to grab tax base as much as population may have done much to prevent their decline to begin with.